Looking back at all the challenges a military installation face, both in war and peace time, it would seem that the Navy with its waterfront installations might many more in both its efforts to help people at sea as well as to protect its installation from both land and sea problems.

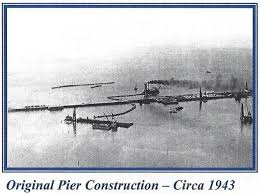

It is a tribute to the planning and orderliness of the US Navy that there are few serious accidents that have occurred at what is now Naval Weapons Station Earle. When built during World War II in 1943, the base was known as Earle Naval Ammunition Depot. Today, it is Naval Weapons Station Earle with its waterfront complex in Leonardo and its headquarters in Colts Neck.

The Navy installation spans more than 11,000 acres in Monmouth County, including more than 100 miles of rail tracks built to accommodate locomotives, flat cars, box cars and more between the Leonardo pier and the headquarters and other buildings and facilities in Colts Neck.

There are three piers on the Leonardo side, and in the beginning, in addition to Navy and Marine personnel, the Coast Guard also reported here during wartime, and were accommodated for housing at the Coast Guard base on Sandy Hook. With merchant vessels also carrying ammunition in addition to Navy ships, the Coast Guard’s work efforts intensified and by July of 1944, there were four Coast Guard officers and 60 enlisted men reporting for duty at NAD Earle.

It was the bravery, quick thinking and swift action of Navy and Coast Guard personnel and rugged equipment of the US Navy that averted an accident that had the potential of wiping out a large percentage of lives and homes in the Bayshore.

One sailor with his crew almost single handedly prevented that disaster because of his own bravery and their swift action.

It happened one cold night in January 1945.

Lieutenant Commander O’Pray was at home and in bed when he received a call from Chief Boatswain Alexander Gross. Gross reported to the dockmaster there was a vessel on fire just east of the pier area in the vicinity of Sandy Hook.

It was around 1 a.m. in the morning; there were extremely rough seas, and gale winds blowing throughout the area between 50 and 60 miles an hour.

O’Pray’s first orders were to get all the rail cars moved from the pier area. The cars were loaded with ammunition at this time eight months before the end of the war, and the commander made safety of personnel and land his first priority. Next, the dockmaster ordered that action be taken to get the ships berthed at the Pier away from the area, clear of any danger and ordered the largest yard boat to be in charge of that directive. Next, Lieutenant Commander O’Pray ordered that no fewer than three of the yard vessels head out to the stricken burning vessel and assist in every way possible in putting out the fire and rescuing personnel.

One of those three vessels sent out in the middle of a dark night, in the height of heavy seas and gale force winds, was YTB216, a tugboat.

Named the Cochise, and under the control of R.L. Tooker, was this the right move to make?

Did R.L. Tooker respond in the way he should? Stay turned for Part II of the story…