The most difficult part of writing my book, The ABCs of Highlands, was in narrowing down the numerous choices I had to tell stories about people who lived, loved and made such a difference in Highlands.

Almost every letter was a challenge, but when it came to W, it just seemed right that in this first ABCs, the W should be Jimmy White, husband, father, native, clammer, teacher, mayor and so much more. There was not a soul in Highlands Jimmy did not know during his years as mayor. And there wasn’t a student at the public school who didn’t love Mr. White and the fascinating stories he told about fishing, clamming, and Highlands along with his getting the academic messages across as educator.

If you like this story and want to see the rest of the letters from A to Z, there are still books for sale and you can check that out on www.venividiscripto.com. In the meantime, enjoy meeting Jimmy White once again.

He was a teacher at the Highlands Elementary School, beloved and respected. He was admired for his ability to interact with his students and keep them interested and educated in every subject from history to marine life. The James T. White Memorial Award for Environmental Science was established in 1991 and is awarded annually to two sixth grade graduates of the school who show an aptitude and special interest in the environmental sciences.

He was mayor of the borough for seven years, always in the headlines, often controversial, sometimes battling with other council members.

But when you hear the name James T. White, it isn’t his educational abilities that first come to mind. Nor is it his political acumen.

It is his expertise and lifelong fight for clammers, clean water, and the clamming industry.

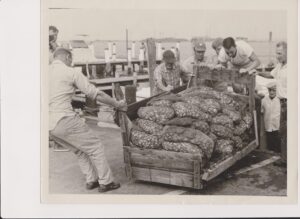

By the same token, you cannot talk about clamming, especially clamming in Highlands, without hearing the name Jimmy White. He’s right up there with the Hartsgroves, the Loders, the Parkers, the Matthews, the Cottrells, the Johnsons, (see story on Mickey Johnson), the Voorhees, the Maxsons. They were the same names as clammers at the turn of the 20th century, a group who banded with clam openers and went on strike in 1910 to demand a minimum of 60 cents a bushel from the wholesalers, asking for an increase of the former 50 cents a bushel because of the high cost of living.

Generations of all those families still make Highlands their home, and scores of them continue to make clamming their business.

Jim is a native and the son of a native. He’s also the grandson of a clammer who first moved to Highlands because of his vocation and love for the arduous and sometimes insecure life of a clammer. Jim White inherited those generations of love for the Highlands waterfront from both sides of his family. He traced his lineage in borough clamming to the late 1800s when his maternal grandfather Clarence Burlue was a waterman and had his clam business on Miller Street. Burlue’s son continued in the business as did Jim’s father, who passed on the intricacies of the rivers and the skills of clamming to Jim. Jim lived in that house on Miller Street.

Jim clammed from his childhood, working summers at the trade to earn his degree from Monmouth College. After earning that degree in education, he continued clamming as well during the 17 years he taught in the same elementary school he himself had attended and where he later served on its Board of Education.

While Jim had a number of diversified interests, served in the military and was active in both the American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars, clamming was always uppermost in his mind. His students in the classroom were taught well on the importance of clear waters and the impact of pollution on the seafood industry. His political years were filled with his battles at all levels of government, his campaigns for cleaner water, a clam depuration plant, educating the public on the trials and tribulations of a clammer, how the industry was hit by numerous setbacks and downfalls, from polluted waters from sewage backups or broken pipes, to foul weather, blights, and government action that at one time halted the direct sale of all shellfish.

When pollution grew as a problem, depuration continued to be considered a possible solution. Jim was a strong advocate of it, explaining how clams and other shellfish clean themselves, how they can be put into pure clean water and left alone for a couple of days, then, with the help of ultraviolet light, become purified.

It was in 1968 when, six months before he became mayor, Jim White first made public his idea for depuration. In January, the Baymen’s Association where he was secretary, asked that the property they were leasing from the borough for a dollar a year at Miller and Fifth Streets include an option to buy so they could build such a plant.

Shortly after becoming mayor in July, he introduced an amendment to the borough’s codes that would permit a clam depuration plant as a permitted use on the shoreline. But his nemesis on the council, former Mayor Neil Guiney and others , said no to the idea. Guiney said White was a clammer, secretary of the Baymen’s Association, the group of clammers advocating a plant, and that put White in conflict of interest. The borough attorney would not give an opinion on which official was right; he said he had to study the matter further. The fight went on for many years, through many councils, zoning and planning boards and for many different arguments.

In the end, It was Bob Soleau who was the first businessman to put the depuration plant into use in New Jersey. In fact, he was the first businessman to have a privately owned depuration plant in the entire country, one that was supervised by the state to ensure it did what it promised to do. His plant was just below the Highlands bridge, just underneath Moby’s adjacent to Bahrs Restaurant. Soleau opened his plant in April 1974, the month after all the waters around the Bayshore were closed to clammers because of pollution. The state said only clams harvested and passing through the state-approved depuration process at Soleau’s could be taken.

Soleau sold Moby’s to Ray Cosgrove and his partner at Bahrs Restaurant after the plant had been closed in May 1975. Cosgrove planned to reopen it and expand the famed Bahrs Restaurant to include Moby’s outdoor dining overlooking the Shrewsbury River as well as operate the clam plant when it was reopened.

From the beginning, Jim White didn’t like Bob Soleau‘s plant. He called it self-serving, a money-making operation that would take advantage of the clammers who would be forced to go through him before they can sell their clams. Jim persisted in fighting for a second depuration plant, and when Soleau’s was approved he said the second one would be open within a month. Soleau scoffed at the idea.

Jim didn’t get all the necessary permits to keep his self-made deadline. But it did not stop him from trying, continuing his fight for what he knew was best for Highlands, the river, and the clamming industry. He constantly beseeched the state to take action, provide funds, do something to save the river, the clams, and the industry. Others saw it as a lost cause. Jim White never gave up.

Jim retired from teaching but continued clamming, was owner-operator of the Shrewsbury River Clam Company and had his own wholesale seafood business. He had already served as mayor from 1968 to 1974 but stepped in again to finish the unexpired term of the late Mayor Bob Wilson. He was council president in 1991, serving with Mayor Ray Ramirez, James E. Smith, Jr., Donald Manrodt, Sr. and Anthony Bucco.

On July 12, 1991, he was in the passenger seat of a pickup truck driven by a fellow clammer and friend, on their way home from dropping clams off in Maryland. They were in Newcastle, Delaware on a Friday afternoon when a car traveling in the opposite direction struck a curb coming off the southbound ramp, bounded into the other lane of the ramp and hit a second car. That car stopped, but the first car spun out of control onto the northbound lane of Route 13, hitting the pickup truck and forcing it into the center lane. There it was struck from the rear by a delivery truck and ended up on its side against the guardrail. Jim White, clammer, teacher, politician, fighter for everything he felt needed to be corrected, lost his battle with life on that Delaware highway.

That same day, back in Highlands, the borough clerk received a notice. Governor Jim Florio would be in town in ten days. His purpose? He was coming to announce that the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey had granted an award of up to $3 million for a clam depuration plant in Highlands.

Jim White never got to see the plant he fought so hard for decades to become a reality for his beloved clammers and their families. But it is still there and active today, decades later. It is named the James T. White Depuration Plant.